conferences

My notes from conference sessions I have attended.

Agile Virtual Summit

June 1-5, 2020

Real Prioritization and Collaboration Strategies

with Jim Benson

Zeigarnik Effect: once we begin a task, we can’t NOT be thinking about it.

“Individuals and interactions through processes and tools.”

Organize your options (your backlog) using the Cynefin framework (obvious, complex, complicated, or chaotic).

Chaotic: FIRE! Put it out, then analyze immediately

Obvious: delegate or automate as much as possible

Complex/Complicated: spend your attention here. Pair, mob, teach, and learn through the work

Improvement

Anti-pattern: Rosy Retrospection. The longer you wait to retrospect on an problem, the more you will discount how bad it really was.

Add Retrospect and We Need To Talk columns after Done on your board.

Place items that you learned something from in Retrospect, to reflect on later and cement the lesson. This is periodic improvement.

Place drastic (chaotic/FIRE) items into We Need To Talk after Done. Don’t wait to retrospect on these, do it as soon as things are stable. This is continuous improvement.

High-Performance Teams: Core Protocols for Psychological Safety and Emotional Intelligence

with Richard Kasperowski

Ask yourself: “What is the best team you were ever on?” What was it about that team that made it great? Probably trust, safety, and fun.

We mostly ascribe these factors to luck. They just happened to put the right people together. It’s a roll of the dice. But These things can be fostered on purpose for any team!

Team Emotional Intelligence (TEI) ->

Psychological Safety (PS) ->

High-Performing Team (HPT)

Core Protocols

Team Emotional Intelligence can be formed/enhanced through the use of the Core Protocols.

- success patterns for interactions between people

- discovered in a similar way to PS from Project Aristotle: they were naturally occuring behaviors observed on existing High-Performing Teams.

- they create a level of safety that can liberate a team’s power of collective genius

A High-Performing Team performs objectively better than other teams doing similar work. (It’s not intangible or subjective!)

It’s quickly becoming standard to measure (software) teams using the four key metrics from DevOps (deployment frequency, lead time, MTBF, and MTTR).

Aspects of HPT:

Positive Bias

- no negation (yes, and)

- even when they disagree with an idea, they pretend it is valuable at first

- to make space to explore it (curiosity!) and

- to not discourage ideation in the future

Respect for team members’ ideas unlocks the team’s genius.

Freedom

Freedom is the basis of any great culture. HPT members have freedom. (This includes the freedom to not be on a HPT!)

Protocols: Pass/Unpass, Check out. A team member may opt out of any activity (pairing/mobbing, a protocol, a meeting). This is not to say that this won’t have consequences for them and the team, just that they are free to choose.

Self-awareness

Protocols: Check-in, Ask for help, Personal Alignment.

Try a Check-in as a “fourth question” in your next Daily Scrum.

Personal Alignment: “I want __.” This is way open-ended. If it stumps you, try narrowing the possible responses to a list of virtues:

- Self-Awareness (default; if you don’t know what you want, you want self-awareness)

- Integrity

- Courage

- Passion

- Peace

- Presence

- Self-Care

- Fun

- Wisdom

- Health

Connection

Protocols: Self-awareness (Check-in, Ask for help, Personal Alignment) plus Intention Check and Investigate.

Intention Check: “When you did/said __, what was your intention?” -> “I’m curious—will you tell me more about ___?”

It may make people uncomfortable to say, but an HPT is founded on LOVE. Connection is a big part of that.

Productivity

The Decider protocol (thumbs up/down, flat hand).

In the case of a thumbs down, the voter can offer a suggestion that would get them to a thumbs-up.

The flat hand indicates that you trust the team’s collective judgement either way.

Error Handling

“A HPT navigates conflict.”

One of the protocols is a Protocol Check—error handling is baked in.

Continuous Teaming

A team that uses the Core Protocols is continuously integrating their team, actively fostering the above qualities of HPT.

Management in Agile

with Peter Green

VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous)

Parker Palmer’s Tragic Gap

We realize that things are not as they should be, and respond in two ways:

- Caustic Cynicism, in which we leverage the system’s weakness to our personal advantage

- Ineffective Idealism, in which we get caught up in hope, but take no action.

Both of which (ironically) lead to the same result. In order to actually move the system forward, Palmer asserts that we should instead Stand in the Gap.

David Marquet’s Turn The Ship Around

The poorest performing ship turned things around when Marquet stopped giving orders. Instead, staff brought their ideas to him:

- I intend to __.

- I’ve done the following due dilligence: __.

- Here’s how it aligns with our vision/mission/strategy: __.

These map directly to Pink’s factors of motivation (Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose, respectively).

Problems and work in a complex domain are dependent on context. We cannot simply copy processes/procedures from one complex domain and expect them to work in another. (See also Cargo Cult)

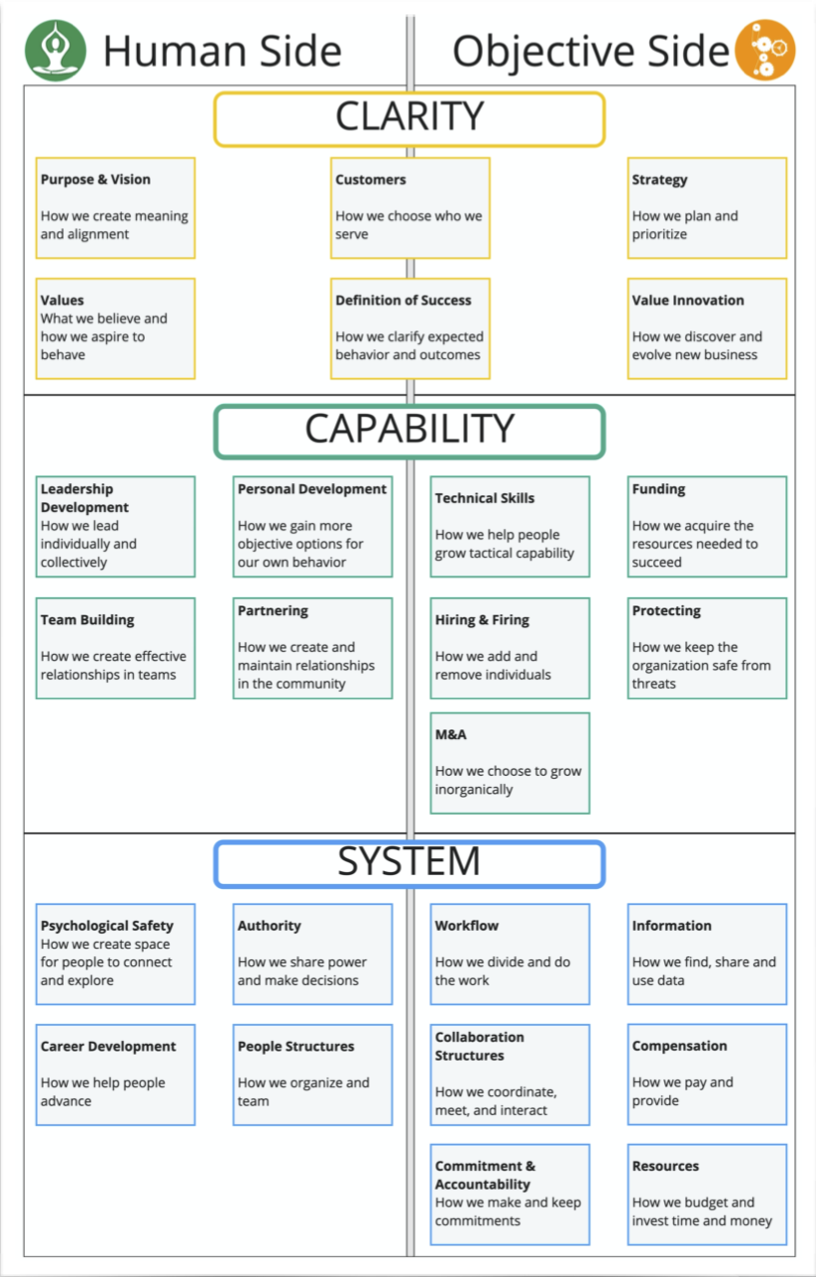

The Three Jobs of Management

If we’re no longer giving orders, what do we need to trust the team to make the right decisions?

- We need Clarity between the team and the org on what work we have to do

- We need the team to be Competent and Capable.

- We need the team to surface Information that will help to improve the org.

This forms the focus for the work of managers in an Agile organization:

Create Clarity

Increase Capability

Improve the System

As much as possible, let the teams themselves be responsible for things that don’t fall neatly under these headings.

Along Two Dimensions

The Three Jobs apply along both the Human and the Objective dimension. Examples of how work maps to these jobs and dimensions:

Overlap with other roles

There is some overlap in this work with Scrum roles. A Product Owner will work to Create Clarity around their product, for instance. A Scrum Master would certainly be involved in Improving the System and Increasing Capability (especially on the Human dimension).

Managers should partner closely with PO/SM for Scrum Teams whose members report to them. For example, when Creating Clarity, the manager and PO may collaborate on setting the team’s Purpose, Mission, and Vision, while the PO would take on Strategy, Customer Segmentation, and managing the Product Backlog on their own.

What if I’m not a manager?

You can still use the Three Jobs to own the work you do have a say in, while working to expand your influence.

Q: How does this work with SaFE?

A: “I have yet to see it work” for the Complex domain, it seems better suited for Complicated work (“I don’t know this, but we have an expert who does”).

Q: Where’s the line between the work of a Scrum Master and a Manager?

A: It depends on the team’s capabilities.

Leadership Agility model

Managers progress from Expert to Achiever to Catalyst. (Does this line up with ShuHaRi?)

The Power of the Pivot: Agile companies are built for times like these

with Howard Sublett

- The earliest maps from history show complete certainty about the world, an attempt to convey the authority of the person who made the map.

- When people got over themselves and began indicating areas of uncertainty on their maps (thar be dragons), it sparked a sense of adventure for people to begin exploring.

- Saying “here’s something we don’t know” in public leads to action.

Draw Your Seamonsters

- declare what you don’t know

- push decision-making to the edges/front lines of your organization, so your people are inspired to explore!

A Deeper Dive into the Scrum Master Role

with Richard Cheng

Five qualities to look for in a Scrum Master/Agile Team Coach

- Knowledge

- Experience

- Coaching

- Facilitation

- Servant Leadership

A good Scrum Master is always on the verge of getting fired.

—Ken Schwaber

(This is likely because a good Scrum Master has to be able to be direct and have difficult conversations with managers and leaders.)

How to evaluate the work of a Scrum Master?

How is the Product Owner doing?

- Is the Product Backlog clear and in good order?

- Are they setting effective Sprint Goals?

- Are they transparent with the Stakeholders and Team (on their vision, roadmap, progress, etc.)?

- Are they balancing feature delivery with the reduction of technical debt and other risks?

How is the team doing?

- Are they using good agile engineering practices? (TDD, automation, pairing, etc.)

- Do they self-organize and collaborate well?

- How do they rank on the DevOps Four Key Metrics?

How is the organization doing?

- Are communication barriers between departments or other silos coming down?

- This is typically Agile Coach territory, but the Scrum Master should still have a seat at the table.

The Scrum Master job

Is it a full-time job? Yes.

Should a Scrum Master work across multiple teams? No. (Remember that Focus is a Scrum value)

Filling more than one Scrum role

Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Development Team member are three different skillsets/mindsets.

Can a Product Owner become a good Scrum Master? Yes, but only once they have unlearned the Command and Control mindset and embraced Servant Leadership.

Is the Scrum Master doing a good job?

- Is the team repeatedly making the same mistakes (production bugs, overplanned sprints, etc.)?

- Is the team repeatedly encountering the same issues (external to the team)?

Or, are they improving?

Scrum Master’s Progression for Solving a Problem

- Did it come up in the Retrospective?

- Did you discuss its impact?

- Did you identify the root cause(s)?

- Did you propose a solution?

- Did you try it?

- What were the results?

- What can you do next?

Q+A

On The Agile Coach/Scrum Master relationship: In general, an Agile Coach should coach Scrum Masters on their work with teams, and partner with them on organizational issues. It is not recommended for Scrum Masters to report to an Agile Coach.

On Scrum Mastering while remote: Using the right tool(s) have become much more important in remote work—keep it simple, though. Also, create and maintain good Working Agreements.

On breaking into the Scrum Master scene: jump onto a team and get started!

The Scrum Master doesn’t stop their team from failing. Rather, they ensure that the team learns from their failures.

Are We Really a Team?

with Chris Li

A team is a small number of people (<10) with:

- complementary skills,

- a common purpose,

- a common working approach,

- common performance goals, and

- mutual accountability to one another

Complementary Skills

- the right mix of skills

- technical skills, BUT ALSO skills in

- problem solving,

- decision making, and

- personal interaction

A Common Purpose

- sets the tone for the team’s work

- a source of motivation

A Common Working Approach

- developed together by the team, not imposed from outside (eg, by a manager)

Common Performance Goals

- should be tied to purpose

- behaviors and habits are more effective than target metrics

Mutual Accountability

- promises the team members make to each other

- rooted in commitment and trust (not blame!)

By promising to hold ourselves accountable to the team’s goals, we each earn the right to express our own views about all aspects of the team’s effort and to have our views receive a fair and constructive hearing.

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team

Be vulnerable around one another

Without Trust, team members cannot have transparency and the effective communication that comes along with it.

(Not “trust” as in, “I trust you to get this done” or “I trust you to do a good job”. If you trust someone, you can be vulnerable and open with them.)

Passionately debate the important stuff

Without Conflict (AKA Creative Tension), there can be no unfiltered passionate debate. Without Conflict, people’s best ideas are not available to the team.

Make decisions with clarity and confidence

Without Commitment, the team will delay making decisions and taking action.

Call each other out when it’s needed

Without Accountability, resentment will grow within the team, and their leader/manager will become overburdened with babysitting duties.

Focus on winning as a team

A team succeeds and fails together.

“I got my stories done” == “The hole is on your side of the boat”

Q+A

Imagine bringing a new person onto your team. If that person asked you about your team’s purpose (or workflow, or performance goals, etc.), how would you answer? How would your teammates answer? Do this thought experiment before you actually have a new team member to onboard.

“Human APIs” between teams

When someone behaves badly, and their colleagues say “oh, that’s just how they are”, that’s a smell.

How Limits Empower Your Agility

with Diana Larsen

Bob Martin has shown how programming has advanced over decades thanks to increasingly stricter limits in programming languages. Structured programming, OOP, and FP each introduced constraints that allowed programmers to focus on adding capability rather than on mitigating errors.

Larsen’s premise here is that the same principle, that constraints enhance capability, applies to your team’s agility as well.

Did you know? The term “Knowledge Work” was coined by Peter Drucker.

The Agile Fluency model

Fluency = unconscious competence.

The skill/attribute comes naturally, rather than as the result of applied effort. This is the result of consistent practice!

Pre-agile: Command and control, work (as tasks) is assigned to workers by managers. Decisions come from the top-down.

Focusing: The team thinks and plans in terms of the benefits their sponsors, customers, and users will see from their software. Scrum, non-technical XP

Delivering: The team can release their latest work, at minimal risk and cost, whenever the business desires. DevOps, CI/CD, XP, Kanban

Optimizing: The team understands what their market wants, what your business needs, and how to meet those needs.

One of the biggest challenges in enabling Optimizing fluency is giving the team true control over its product direction. The distinction between an Optimizing team and a Delivering team is that, within the constraints of its charter, the Optimizing team makes its own decisions about what to fund and where to focus their efforts. Managers need to delegate this power to teams, which is often a difficult change for organizations.

This stage is particularly disruptive to traditional organizations. It often requires reorganization and the political will to make it happen. Titles, promotional paths, etc. get shaken up.

Leaders tend to like it; middle managers tend to fear it.

Strengthening: The team understands its role in the larger organizational system and actively works to make that system more successful. The future of agile. (Sometimes marked by cutting-edge techniques like Team Self-selection and Open Space strategy meetings)

Each of these zones adds limitations.

For example,

- Product Backlog size

- User Story size

- Work in progress

- Working done individually

- Reteaming

- Decision-making by managers

- Functional departments/silos

…are all limited in an Agile environment.

When undergoing an Agile Transformation

LIMIT your organization’s focus to improving one of these zones at a time.

Think of each new limit as a tradeoff.

“We’re giving up __ for __.”

- WIP for Throughput

- Feature count for quality

- Control for resilience

- Certainty for innovation

When you argue with reality, you lose, but only 100% of the time.

Understand the organization’s reality and its limitations when choosing the level of fluency to target.

Don’t impose change from the outside. By involving people in the creation of an improvement plan, you create buy-in and motivation to carry it through.

Q+A

Cynefin

Simple / Obvious: Problems are easy to solve and have one best solution. You can categorise and say, “Oh, it’s one of those problems.”

Complicated: Often made up of parts which add together predictably. Requires expertise to solve. You can analyse this problem if you have the expertise.

Complex: Properties emerge as a result of the interactions of the parts. Cause and effect are only correlated in retrospect. Problems must be approached by experiment, or probe. Both outcomes and practices emerge.

Chaos: Resolves itself quickly, and not always in your favour. Often disastrous and to be avoided, but can also be entered deliberately (a shallow dive into chaos) to help generate innovation. Problems need someone to act quickly. Throwing constraints around the problem can help move it into complexity. Practices which come from this space are novel.

Disorder: We don’t know which domain dominates, so we behave according to our preferred domain (think PMs demanding predictability even when we’re doing something very new that we’ve never done before, or devs reinventing the wheel rather than getting an off-the-shelf library). Often leads to chaos when the domain resolves (I know least about this domain, but it’s way more important than I originally thought it was!)

(Can we use this to refine a product backlog?)

Designing Great (Virtual) Meetings

with Paul Tevis

If you want to understand an organization’s leadership, strategy, and culture, sit in on their meetings.

Meeting Design

- do simple things well

- pay attention to the signal to noise ratio

- Provide a clear purpose/desired outcome for the meeting up front

- Make the meeting’s structure and engagement obvious

- Support participants’ energy and attention

Purpose

A meeting’s purpose should be a verb phrase (eg, “generate ideas for…”, “share perspectives on…”, “scaffold the code for…”).

Repeat the purpose early and often throughout the meeting.

Share it in a slide or other visual.

Put it in the chat.

(In general, use the meetings’ chat as a narration of the meeting.)

Work outcomes: decisions, lists, etc. Human outcomes: awareness, understanding, persuasion, buy-in, etc.

Structure and Engagement

Match the meeting’s structure and engagement to its purpose!

For example, idea generation should probably involve some silent brainwriting (and probably shouldn’t look like a mob programming session).

And a decision-making meeting would

- have participants form groups to analyze and plan

- have groups present their findings

- poll the room to converge on a direction

Make the meeting’s structure and engagement obvious.

Anyone in the room should be able to stop the meeting (or prevent it from starting) if they do not understand its purpose or how they should participate.

Upgrade: Provide material that explains these clearly (not just verbally).

Design for the engagement that you need.

Use Google Slides (or PowerPoint) interactively! Have some slides that participants can write on/add their ideas.

Keep it Simple

Watch for resistance from complicated setup or tools

Question your favorite tools—are they the right fit for the meeting?

Use a non-technical solution if you can (eg, showing a fist-of-five rather than using a polling app)

Breaks

Take this seriously—people’s attention is fragile and expensive.

For every hour of meeting, and average of 15 minutes of breaktime. (10 minutes for in-person meetings—Zoom fatigue is real!)

No break should be shorter than 10 minutes.

Use a visible timer.

Restart firmly on time.

Upgrade your breaks:

- Ahead of time, poll attendees for their favorite songs and make a playlist of them. Play the playlist during breaks.

- Share a page from a coloring book, and have the attendees color it using Zoom’s annotation tools.

Check in on attendees’ energy levels often, maybe using a poll to eliminate social pressure.

Q+A

Senior leaders sometimes hijack meetings. It’s going to happen. Try to get some intel ahead of time on who is likely to do this, and learn about their goals. Try to get their buy-in, so they don’t hijack.

Facilitation is done from a posture of invitation, not control. Improv skills come in very handy here.

To make chat-based input more safe, have people

- type their responses,

- show their hands until everyone is done typing,

- then hit Enter together

If anonymity is important, have them set their Zoom name to blank before using chat.

Find out what is making the group unsafe, and remove it. Have leaders give their input last. Don’t make it too safe, though—feeling some vulnerability when meeting is a creative sweet spot.

If someone is distracted during the meeting (looking at their phone, typing, etc.), invite them to leave as needed. No one should be captive to a meeting when their attention needs to be elsewhere.

Use Resistance

(from a leader/authority): “How do you know __ works?”

(the Aikido move): “Tell me more about your experience with __.”

Expect to spend about 2x of the meeting time to prepare for it (if it’s not a meeting you’ve held before).

Use Agile on Yourself

with Lyssa Adkins

Personal Agility

- What really matters? (up to 4 things)

- What did I do last week?

- What could I do this week?

- What is important or urgent?

- What do I want to get done?

- Who can help?

The magic of looking back; the perseverance to move forward

with Kim Brainard

Many organizations say they value “innovation”, but their culture breeds anything but. (Fear of rejection, lack of ownership, etc.)

- 70% of initiatives fail

- People don’t know who’s responsible for a given initiative

What suffers more breakdown in your organization?

- Products: 5%

- Processes: 32%

- People: 62%

Never fear rejection or acceptance

Try the next right thing. Don’t worry about whether people like it (or whether they like you).

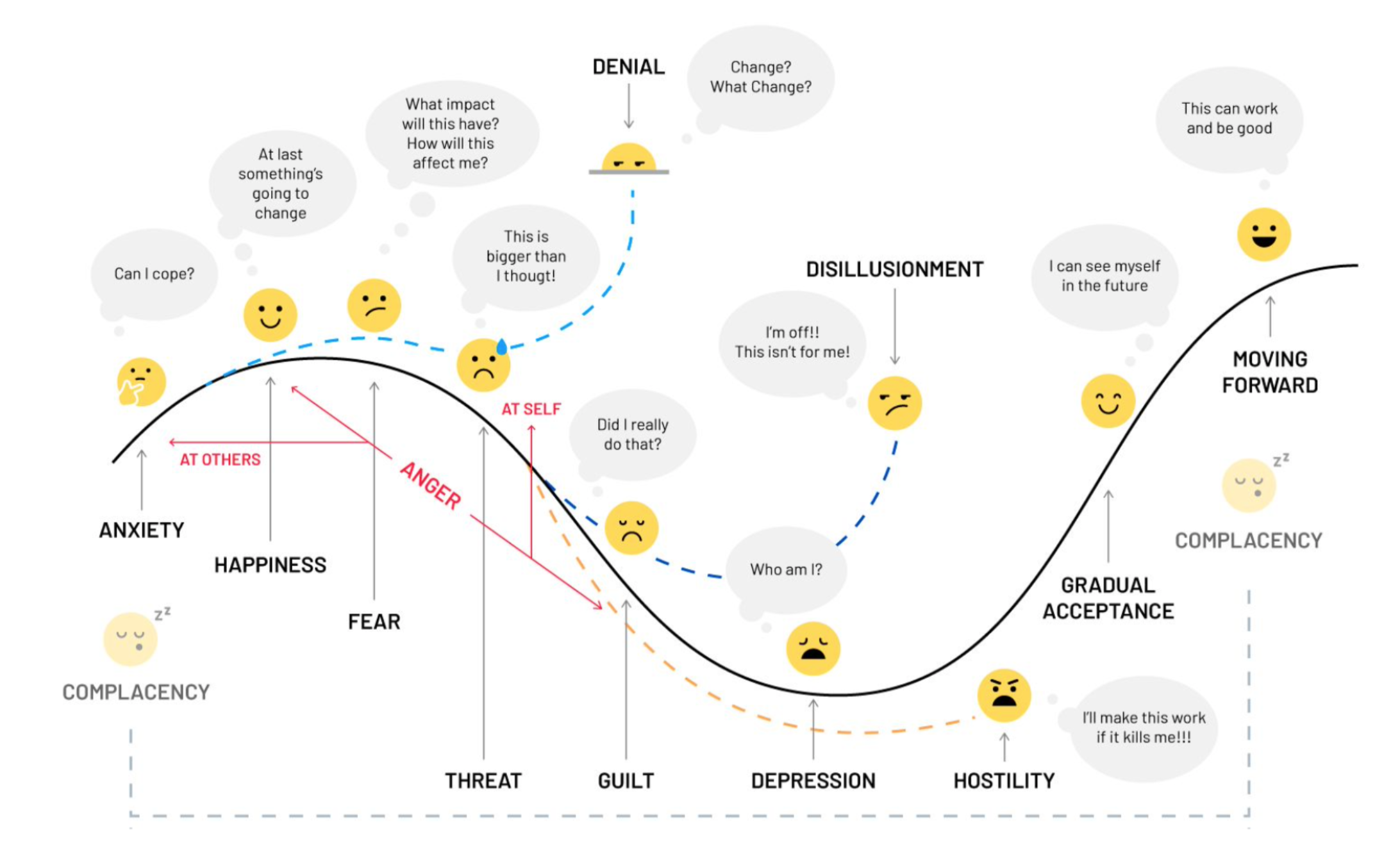

The J-Curve

(also known as the Satir Change Curve and the “Project Valley of Death”)

Agile is a mindset, not a methodology.

There is no repeatable method for learning and discovering.

Don’t just think outside the box—step outside the box.

Meetings

Time

- 3 (non-Scrum) meetings per day, at most.

- 45 minutes (not a whole hour)

- Start promptly at the top of the hour.

Choose your presence

- listen more than you talk

- no soapboxing

- STOP taking minutes! (just write down important takeaways)

- Leaders set the tone by their reactions to events (eg, fires, failures)

- Empower people, stop backseat driving, and let go

When pressures increase, honest communication stops.

Learning

Leaders and staff must spend time learning together.

If there are no relationships, there is no culture.